The Beatles Sucked (A Brief History of Rock)

February 7th, 1964 was a tragic day for American rock and roll. On that day, four smirking emissaries of the banal touched down at LaGuardia airport, U.S.A. for the very first time. In their Cuban heeled boots and women’s haircuts, they calmly stepped into a national hysteria. Still reeling in shock from the murder of its young president a few months earlier, the country was undergoing the violent throes of forced racial integration amid the roiling perils of the cold war, which seemed to be conspiring toward nuclear annihilation.

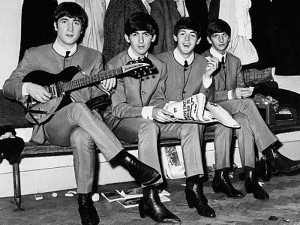

During this national turmoil, an unremarkable British four-piece merseybeat combo launched (or perhaps, its more accurate to say “were launched into”) a campaign to harvest maximum profits from the historically impenetrable U.S. pop music market. Initially, critics considered their music mindless dribble for children. A few years later, they were hailed as geniuses of thought and song. Mainstream luminaries like Leonard Bernstein and Frank Sinatra gave effusive praise. By the time the last surviving members of the Beatles were into their dottage, their work was enshrined at the top of the canon, sacrosanct.

Today, it is generally accepted that the Beatles revived the dying music of rock and roll and were the greatest, most significant, most influential band ever. This belief is a fallacy of myth. If you ask: what did the Beatles do differently? The acolytes will tell you that they were the first rock and roll band to write their own songs or play their own instruments or make sophisticated rock music or write deep lyrics. None of that is true. In reality, the music of the Beatles was often mediocre at best. A lot of the time they sucked.

The history of the Beatles is a story so well-known and oft told that it had already become mythic while the principals were all still alive. Its been the subject of countless books, documentaries, and dissertations. Posthumous movie tributes include the irreverent Rutles project (backed by George Harrison) followed by Hollywood’s druggy, turgid 1978 love letter “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band” and the more sober and reverent recent iterations (“Backbeat,” “Nowhere Boy”) that were tied in with a massive public-relations campaign to raise public awareness of the Beatles’ greatness. 1995 was the kick-off year, with the weighty six hour “documentary” tribute broadcast on ABC and the vomitous cash-grab “Free as a Bird” single marking the beginning of a prolonged period of more re-packaging of the same product

A central tenet of the Beatles Myth is that they when they arrived, rock and roll in America was on its last legs, dying from a sense of diminished possibility and producing dull songs with hopelessly lame lyrics. But this was not the case. An examination of the field provides some explanation for the fallacy.

Although only a decade old, rock’s history was already rife with tragedy and controversy. When the Beatles touched down in February, 1964, it was almost five years to the day that Buddy Holly perished in an airplane crash in Iowa, alongside Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper on the doomed Winter Dance Party Tour. The death of the Crickets leader at 22 and his taut, melodic evocations of exuberance and sweetness with anxious undercurrents was a huge loss for the emerging genre. Holly was an accomplished guitarist, level-headed, prolific and ambitious, modern in outlook and sensibility. His short body of work shows enviable growth and breadth, as well as the confidence to experiment with sound and increasingly mature lyrics.

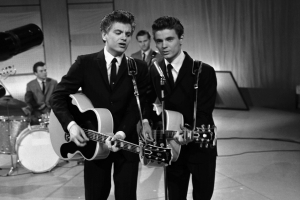

The Everly Brothers (Don and Phil) were born into a country music family in Kentucky and grew up singing and playing acoustic guitars together. They were thoroughly steeped in the country and pop music canons. Their technique was to use vocal harmonies based on parallel thirds. Don sang baritone and Phil sang tenor. Working with a husband and wife writing team, their first hits were country-styled rock songs that broke the top 10 in the United States and U.K. Their first single “Bye Bye Love” was released in March, 1957 and hit No. 2 on the pop charts behind Elvis Presley’s “Teddy Bear.” Phil was still a teenager, Don just a couple years older.

The brothers had fantastic voices and harmonies, impeccable style and rocker haircuts. They toured extensively with Buddy Holly, with whom they shared songs, and were responsible for transitioning Holly and his band from T-shirts and Levis to sharp suits. The duo began writing their own material to great success with 1961’s excellent “Cathy’s Clown,” (they are backed by the surviving Crickets in the posted clip), whose harmonizing bears an exact resemblance to subsequent early Beatles singles. They expanded more into pop and rock sounds and later a rich period of under-appreciated country and psychedelia. By the time the Beatles arrived, however, their popularity had started to drop off a bit.

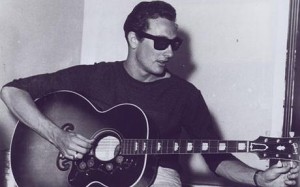

Rock and roll’s greatest lyricist and musical creator was (and remains as the creator still performs live with regularity and occasional blasts of verve) its ultimate king: Chuck Berry. The leader of a black rave-up band in St. Louis, Berry incorporated a good deal of country music into his compositions. His first release was 1955’s iconic, unabashedly hillbilly “Maybellene” (the 1938 recording of “Ida Red” by Bob Willis and the Texas Playboys transformed into a searing ode to cars, speed and sex). It promptly smashed up the charts, initiating a run that saw the black twenty-nine year old emerge as the unlikely, preeminent chronicler of white teenage existence.

Berry made his ringing guitar central to the new music and developed a rhythmic style modeled on boogie-woogie piano. He was greatly aided by his often overlooked band, whose most crucial musical collaborator was pianist Johnnie Johnson. Berry’s unique soloing was inspired by a solo of Carl Hogan, Louie Jordan’s guitar-player. The advanced musicianship and range at play is apparent by the ease with which Berry incorporated jazz or Hawaiian-guitar elements, or could feature r&b on a burner like “Come On,” spooky rockabilly on “Down Bound Train,” then throw out a catchy oddity like “Anthony Boy.”

The lyrics were a kind of magniloquent street-language, sometimes slyly political, sometimes tossing off incongruous references to Beethoven or jazz players like Ahmad Jamal, so dense with verbiage and images that they required the clear diction of Berry’s country music phrasing. A daughter did not just shed a tear, she had “hurry home drops on her cheek that trickled from her eye” as the estranged father pleads with an operator for information in the deceptively tender “Memphis, Tennessee.”

Black rock and rollers were hated and feared by white parents because they made wild, sexual music that appealed to white girls. Black rockers were routinely subject to police harassment and worse. Georgia, flashpoint of the battle for racial equality, was especially terrifying. In Macon, Little Richard was pulled off stage and beaten by police, who yelled “You’re not going to play that nigger music!” Bo Diddley and his band were pulled over by Georgia’s highway patrol, who expected to find liquor. Finding none, the officers pulled guns and ordered Diddley and his band to dance. They did.

On the day before Christmas Eve, 1959, Chuck Berry was questioned by St. Louis police about a fourteen year old prostitute he’d picked up in Juarez, Mexico while on tour and brought back to work at his nightclub. He was arrested and charged with violating the Mann Act and eventually convicted after the first decision was tossed because of the trial judge’s overt racism. The victim took the stand for the second trial and Berry unwisely did the same. Afterward, it was apparent to the jury that Berry had sex with the girl multiple times from picking her up in Mexico to employing her at his club in St. Louis. Although the point was not technically central to the charge, it was greatly damaging and would prove to be a permanent shameful stain on Berry’s career and reputation. Years later, he would claim in interviews that he beat the charge and never went to prison.

Chuck Berry spent the years between 1960 and 1964 as a defendant in court, then an inmate in a federal prison. Scandal and punishment did not deter him from adding to his run. He claimed he wrote the comeback hits “No Particular Place to Go,” “Nadine,” “Tulane,” “You Never Can Tell,” and the astounding “Promised Land” during the stint.

In October, 1963, Berry emerged from prison and briskly resumed business. He would soon watch as the Beatles then Rolling Stones reached sudden fame and critical adulation by playing weak, British-accented versions of his songs. The beneficence of the new pop royalty raised Berry’s performance-rate, but his excellent new singles went straight to the middle, then bottom of the U.S. charts as every utterance and move of the new arrivals was endlessly fawned over by the press. Former colleagues like Carl Perkins found him to be a changed, embittered man. As the sixties wore into the seventies, the great creator of rock and roll gradually shut the cover on his songbook, focusing himself squarely on becoming a self-sufficient journeyman, traveling from gig to gig with only his guitar.

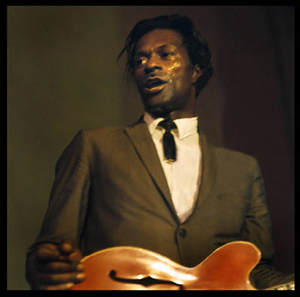

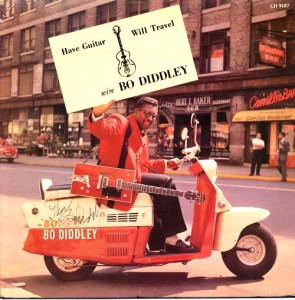

Similar to Berry in influence and innovation was Berry’s equally famous label mate at Chess Records, Bo Diddley, n.e. Elias McDaniel. Like Berry, Bo Diddley was comfortable drawing on a wide range of influences throughout a long career and showed great lyrical talent from the start on releases like the devastating “Who Do You Love?” single in 1956. He was a self-taught guitarist who had started off playing classical violin and trombone. A professional carpenter and mechanic, he built his unique square guitars and created his own iconic beat, among other things. Bo Diddley’s immense influence on rock and roll is still greatly under appreciated and there is much to say about his innovations in music, presentation, design, style, and concept.

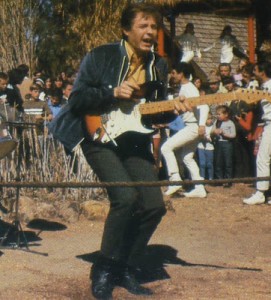

But I would rather watch this video of Bo delivering a jaw-dropping performance of “Hey Bo Diddley” in 1973.

Little Richard quit show business in October of 1957 when, at the height of his powers, he suddenly renounced rock and roll and joined the church. To understand what “Little Richard at the height of his powers” means, you have to envision a concert hall packed with segregated white kids and black kids, integrated by concert’s end, policemen standing guard as the titanic presence of the diminutive, explosive, witty, perverse Georgia Peach exhorts and taunts the crowd into sheer lunacy, ending up sweaty and shirtless, sometimes pantsless, by the time he closes the show.

After effectively ending his career, Little Richard spent the next five years recording and performing gospel music, until he was booked on a a package tour of England in 1962 and resumed playing rock and roll. He found it harder to get his foot back in the door this time. He played a lot in Europe.

Little Richard, Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry all released their first singles in 1955. They arrived on the national stage in the wake of Elvis, who had already smashed a hammer into the glass idols of old (e.g. Perry Como, Glen Miller) with his first explosive single “That’s Alright Mama” in July, 1954. By 1964, however, Elvis was well into his horrid decline into lame B-movie campdom and creative entropy caused by his increasing isolation, megalomania, drug abuse and the inviolable dictates of his management arrangement with the ruthless Colonel Tom Parker (real name: Andreas van Kujik), who put the King in the army for sport.

Jerry Lee Lewis’s career had self-immolated back in May, 1958 when he brought his thirteen year old first-cousin-once-removed/wife with him on his first tour of England, resulting in immediate condemnation by the frantic U.K. press and subjecting the bewildered Lewis (his cultural background did not envisage the union as immoral) to worldwide ridicule, shaming, and the blacklist. England also brought disaster to Eddie Cochran, whose emergent talent was tragically snuffed out when the rockabilly great died in a horrific and entirely preventable taxi accident on the A4 in Chippenham, Wiltshire en route to fly out of London after playing the last date of his first U.K. tour in 1960.

In 1958, the first hard rock guitar was put to wax on “Rumble,” a slow-groove instrumental by Link Wray and the Raymen that featured a searing guitar wailing away before returning to a few sparse, snarling, fuzz-drenched chords. With a thickly distorted D to E change, Link Wray introduced the electric power-chord to rock and roll. Hard rock, metal, and punk would follow. The shock that the power-chord’s first deployment engendered among an unprepared public is difficult to overstate. So menacing was the throbbing instrumental that it was blacklisted by radio stations across the country for fear it would incite teenage gang violence. It didn’t matter (it probably helped). “Rumble” hit the top 20 and sold over a million copies. Nevertheless, the label’s owner didn’t like the group or their song and dropped them. They quickly picked up a deal with Epic Records.

From left to right: Doug Wray, Vernon Wray, and Link Wray (in his army uniform).

From left to right: Doug Wray, Vernon Wray, and Link Wray (in his army uniform).

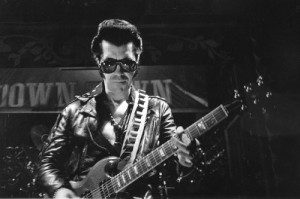

Link Wray, fond of black sunglasses and black clothes, was a half Shawnee-Indian rockabilly-by-way-of-western-swing guitarist out of Virginia. The Raymen were his brothers Doug (drums) and Vernon (rhythm guitar) and Shorty Horton on electric bass. They’d been playing gigs together since 1946. Link was twenty-nine when “Rumble” made him a pop star. He handled it well. He’d survived a lot already. He was born in 1929, the year the stock market crashed. He grew up with his brothers in desperate poverty in North Carolina, faced with horrifying KKK raids and a mother crippled since 11, a father shell-shocked from World War I. When Link was 8, a black circus performer named Hambone showed him how to play blues on a guitar one afternoon.

In 1956 Link Wray lost a lung to tuberculosis he’d contracted in the Korean War. He spent almost a year in a hospital. Upon leaving, he focused his full attention to guitar because doctors told him he couldn’t sing anymore. The band was wearing black leather and ducktail haircuts, playing sock hops when Link started deliberately trying to play notes in a new original way and began cutting up speakers to get the cruder, harder sound he would use on “Rumble.”

For the “Rumble” follow-up, Link traded in his Les Paul for a Danelectro Longhorn with the longest neck of any production-line guitar in existence. The uptempo, faster and more dynamic “Rawhide,” was also a hit, cementing the band’s status as heroes to motorcycle gangs and juvenile delinquents. The record company panicked and pressured them to record corny orchestrated numbers like “Danny Boy” but it didn’t last. Link started singing some of the Raymen numbers around this time, revealing a tough, cracked voice, rough with blues. He paid tribute to his Native-American heritage with thundering instrumentals “Shawnee,” “Apache,” and “Comanche.” But the group’s reputed association with gang violence was too much trouble for Epic and they were dropped again.

The brothers formed their own label Rumble Records and stormed back in 1961, throwing down the challenge of the “Jack the Ripper” single. The lurid title only hinted at the white noise tsunami of an instrumental, bleeding with ahead of its time Hendrix-style feedback. It was a national hit and the band secured a deal with a smaller label that let them have their way.

Link Wray and the Raymen were still producing hits and touring the college circuit as the sixties picked up pace. After the Beatles landed, the bottom fell out. With characteristic tenacity, Link stayed in the game and continued to make incredible forward-looking rock music (see 1979’s “Bullshot” album) and play electrifying gigs at small venues late into a long career. He lived long enough to see his catalog receive renewed worldwide acclaim after “Rumble” was featured in “Pulp Fiction” in 1994. Link was still playing with ferocity and precision in his seventies to large rapturous crowds, often heavy with punks, on the European continent from his homebase in Denmark where he lived with his wife before his death in 2005.

- Link Wray, 1977

As teens, the Beatles idolized all of these musicians. Buddy Holly was a primary influence on the Beatles and their British contemporaries. Holly and the Crickets toured England for a string of dates to packed houses and wild acclaim the year before his death. Fifteen year old Paul McCartney caught one of their 1958 U.K. performances (as did Keith Richards). Decades later, Holly’s songs would be among the first that McCartney acquired ownership of when he started playing the song-royalties market. In 1985, McCartney produced an excellent documentary about Holly in response to inaccuracies propagated by the 1978 biopic.

George Harrison saw Eddie Cochran on his U.K. Tour. A lifetime later, Harrison could still vividly recall Cochran’s effortlessly cool stage presence. John Lennon brought Chuck Berry onto the Mike Douglas show in 1972 and paid respectful tribute to the urbane Berry, who shortly thereafter had his biggest hit ever with “My Ding A Ling,” a bad gag of a song, brimming with contempt for its hippie audience.

About Presley, Lennon said: “Before Elvis, there was nothing.” The summer after their first tour of America, in August of 1965, the Beatles would obtain an awkward audience with the King at his Malibu mansion. Elvis sullenly played a bass guitar and kicked off some Beatles numbers during a brief jam session with John and Paul. He eyed the foursome warily. He didn’t like them or their music and, unlike most of his contemporaries, he would never pretend to.

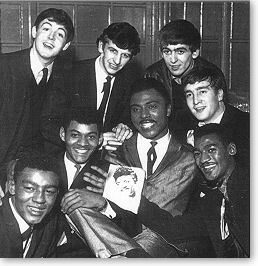

Their closest personal affiliation with any idol was with Little Richard. Lennon and McCartney had been covering Little Richard numbers since their teens when McCartney joined Lennon’s band, the Quarrymen. On his return to rock tour in 1962, Little Richard did a couple of shows backed by the pre-fame Beatles in New Brighton then took them along as support for a two month string of dates in Hamburg, Germany. He didn’t think much of the band’s prospects and declined Brian Epstein’s typically ill-conceived offer of 50% of the group if he would just take their masters to V.J. Records (though he did call the label head on their behalf). He ranked them as imitators, nothing special. The Beatles openly idolized Little Richard throughout their time with him at clubs or shared, cramped accommodations. He got on with Paul and George, but disliked Ringo and especially John, who gleefully announced the arrival of every one of his constant, smelly farts.

By the time the Beatles landed in the United States in 1964, the major music publishing companies were energetically reasserting their control over the pop charts after the breakout of independent upstarts from flyover country. The publishing companies had claimed their greatest prize when Elvis ditched his band and tied himself to Hill & Range (an antique Viennese publishing house) and recorded H&R songs exclusively in exchange for a larger cut. He stuck to the agreement for the rest of his life. Consequently, the Sun sessions are the best material in his catalog.

Saxophone had largely replaced guitar as rock and roll’s primary instrument. The wild performances and sneering, contorted, lascivious faces of rock’s first practitioners, many of them black, that had commanded the tv screens and airwaves a few years earlier had been replaced by the pert gestures and practiced smiles of polished, white teen idols emitting sappy music. Bo Diddley, Little Richard, Chuck Berry and many others had jolted the conscience of the nation’s white teens, who would, at some point, look at a favorite record’s cover photo and think: that guy can’t buy a house on my street. The new rock and roll idols offered teens the chance to pretend to rebel without actually stepping away from the status-quo. The myth asserts that the Beatles offered something different.

Contrary to the Fabians, however, pop and rock music was not stagnant at the start of ‘64. Rhythm and blues continued to yield fresh, more refined and thrilling styles that commanded public attention. Performers like the Isley Brothers and Gary U.S. Bonds cut raucous tracks that blurred the line between r&b and rock and went down tremendously well with the drunk-college-crowd (In 1962, Bonds hired the pre-fame Beatles as his backing band for a tour in England. Like Little Richard, he was not impressed and fired them). The epic and singular James Brown and his band blew the roof off with an amazing performance on the T.A.M.I. show, followed by the deflated Rolling Stones.

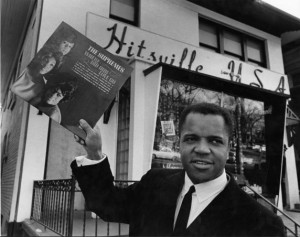

- Berry Gordy at Hitsville USA

Detroit’s Motown was ascendant. An independent black-owned record company, the label handled everything in-house and rolled out star-making acts like the Ford assembly-line where owner/creator Berry Gordy had worked previously. The deeply soulful and complex pop music that resulted was enormously successful and aptly represented the positive ambitions of the label’s driven talent, staff and owner. The mastermind behind the expanding Motown empire was an object of obsessive envy by his West Coast opposite Phil Spector, who was partnered with the East Coast Brill Building collective. Spector used black singers to craft an often dazzling, European-influenced, classical vein of rhythm & blues-based pop music that was also very popular and highly influential.

(Spector would go on to develop a friendship with John Lennon and produce celebrated tracks by Lennon, the Beatles, Leonard Cohen, the Ramones and Starsailor. In 2003, he killed Lana Clarkson by firing a gun he was pointing inside her mouth. Now he sits in jail for the rest of his life and fuck him.)

The saxophone’s primacy was dealt a blow when surf music exploded in popularity shortly after its inception in the early sixties. With roots in instrumentals by Duane Eddy, Chet Atkins, Link Wray, and Bo Diddley, mixed with Mexican classical guitar music, the new guitar-centered music evolved naturally out of a young surfing culture based primarily in Orange County, California. The music was modern and entirely instrumental, often using the newest guitars equipped with vibrato arms and electronic tremolo to make instrumentals intended to approximate the sound and feel of surfing. Sex and social deviance were also popular themes (e.g. the Blazers’ “Beaver Patrol,” the Pyramids’ “Penetration”). Guitarists used effects-switches and rapid alternate picking to create fluid, sweeping, tension-filled solos.

Twenty-one thousand screaming fans showed up to see Dick Dale at the Los Angeles Sports Arena in 1961. By January, 1962 the King of Surf Guitar was drawing crowds of three thousand every weekend at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium with four thousand more waiting outside. Garage bands broke out across the midwest with varying takes on the genre. Hot rod themed instrumentals took off in popularity in regional markets and quickly went national, giving rise to a new sub-genre.

A number of vocal groups in Southern California latched onto the surf phenomena and got famous. The most successful were a family project out of Hawthorne, California consisting of three brothers, a cousin, and a friend. The Beach Boys were a vocal harmony quintet that played instruments and were led by oldest brother Brian Wilson, who arranged and produced the material: Four Freshmen harmonies over watered-down Chuck Berryisms. The music displayed the group’s beautiful harmonies, strong melodies and carefree narratives about surfing and surfer girls. The product proved portable, the band ideal for cameos in the new Hollywood beach movies.

The Beach Boys, surfers none (with the exception of Dennis Wilson), had no real connection to surf culture. With their reliance on doo wop harmonies, they had more in common with the Four Seasons than any nearby surf bands. The new sub-genre of vocal harmony songs was dubbed “beach music.” The Beach Boys were widely disliked by surf enthusiasts for their musical conservatism and trite lyrics, which reduced the dynamic surfing scene to a series of polite, goody-two shoe all-Americanisms. Others noticed that despite all the sunny cheer, many of the songs were colored with an autumnal sadness or gloom, like the haunting “In My Room” or the ethereal “The Lonely Sea,” both co-written and sung by Brian Wilson.

The Beatles were loathed by the surf bands purely for the popularity of their awful, inept music. The Pyramids, a multi-racial, proto-punk unit from Orange County, expressed the feelings of many when they shaved their heads in protest to the Beatles arrival because as drummer Rod McMullen stated in an interview with (now defunct) blog A Modest Conspiracy: “We hated the fucking Beatles.”

The Beach Boys and Beatles were rivals and regarded each other as such, although they were both signed to Capitol. There was no mutual appreciation summit on the 1964 tour. The Beach Boys were a young but established act, hugely successful in the U.S. and England, known for writing, playing and producing their songs. The Beatles campaign for profits on American soil was a broadside on the Beach Boys. Brian Wilson immediately gauged the Beatles as a threat. He was distressed to learn that his own record company was launching the largest publicity campaign ever attempted in the recording industry on behalf of his rivals.

In March of 1964, the Beach Boys moved further into hot rod culture with the release of their fifth album Shut Down Volume II with hits like “Fun, Fun, Fun” and the supposed JFK elegy “Warmth of the Sun,” just as “Beatlemania” began its incinerating sweep across the landscape. The Californians presented a positive, united front, but behind the carefree image, there was a toxic level of family dysfunction at play.

Brian Wilson suffered greatly under the boot of his father, a cruel egomaniac, who was also (to the group’s great misfortune) their business manager. In early 1965, the gifted but fragile Wilson began taking large amounts of LSD, a fashionable drug among the wealthy bohemian set he was running with. It soon triggered a devastating schizophrenic breakdown from which he never fully recovered.

The Beach Boys were thrown by the eruption of Beatlemania and its attendant onslaught of British bands bringing more guitar into the mix. They started coming off as massively un-hip as sixties politics grew more strident. Surf music never adapted the garage band vocals its form cried out for and as the Beach Boys began to look hopelessly yesteryear, the same association attached itself to the relentlessly modern genre they had hijacked.

The Beach Boys’ biggest problems, however, were their leader’s deteriorating mental state and the dark ugliness brought about by drummer Dennis Wilson’s escalating debauchery. Despite these obstacles, the Beach Boys managed to put out their masterpiece single “Good Vibrations” and album Pet Sounds as well as the excellent Carl Wilson helmed follow-up Wild Honey and a couple other great albums before the madness, destruction, and death left too dark a stain.

_____

_____

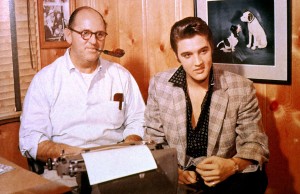

In February, 1964, the Beatles and Beach Boys were rivals but they were also very much on the same team. Both groups were mediocre instrumentalists relying on old-fashioned vocal harmonies to carry their songs. While the Beatles may have trumpeted their rock and roll influences, they were just as heavily invested in the old-time styles of London music hall and Tin Pan Alley. This musical direction came about after the arrival of Brian Epstein, age 27, in October of 1961. Born into a prosperous Jewish family, he had tried various careers and ventures with no success. He had really always wanted to be a dress designer, but this profession, as well as Epstein’s homosexuality, were forbidden pursuits in the eyes of his parents. After he saw the Beatles play a sloppy set at the Cavern, he promptly became their manager, despite having never managed an act before in his life.

By the time he took on the Beatles, Brian Epstein had survived repeated public disgrace after scandals related to his homosexuality and desires for attention and anonymous gay sex. He was working the music desk of his father’s department store in downtown Liverpool, where he had developed a fine ear for picking out which schlocky showtune single would become a hit any given week. Epstein had no interest in rock and roll, but he went on to affect it profoundly through the Beatles and other merseybeat bands that he picked up after them, like Gerry and the Pacemakers, who peddled soft, sweet songs, similarly distinct from rock and roll, and were also enormously successful.

Brian Epstein overhauled the Beatles entire direction, appearance, and presentation. From the very beginning of his association with the middling foursome, the shy, polite and mannered Epstein told the band with unflinching certainty that they would be world-famous.

There is a huge gap between the raw rock and roll that the Beatles professed to admire and much of the stuff that they went on to record. Even Elvis at his corniest wouldn’t have touched most of these numbers. From the awful “Love Me Do” and on to such lauded schlock as “Something,” “Penny Lane,” “Hello Goodbye,” “Got to Get You Into My Life,” “A Little Help From My Friends,” “When I’m Sixty-Four,” “Mr. Kite,” “Yellow Submarine,” “Obla-Di, Obla-Da,” etc., any mindful listener is continually forced to deal with the Beatles’ need to sing jaunty showtunes that have nothing to do with rock and roll. McCartney was the worst purveyor of this slop. The band was frequently at his disposal because Lennon was not prolific and spent most his time off the road in narcotized sloth.

The true opposites to the Beatles and Beach Boys were the young, raw garage bands breaking out across the United States. Inspired by the same first wave rockers as the Beatles, the garage bands had the benefits of sharing a common cultural heritage with their heroes and lacking any interest in London music hall showtunes. They were more tuned into r&b, because they often played the same raunchy frat-rock circuit that hosted acts like the previously mentioned Gary U.S. Bonds and Isley Brothers. Early garage bands used the same synchronized dance moves as the r&b acts and similarly embraced the raw aesthetic of live performance in their recordings, which often featured audience noise. While the Beatles were constructing sweet ditties and the Rolling Stones were copying Chuck Berry and mimicking blues, young American rock bands were building their own niche in the domestic market.

The new rock music of 1964 is exemplified by two songs that were massively popular with the national teen audience right before the Beatles arrived and screwed everything up.

_____

In December, 1963, the Kingsmen of Portland, Oregon stumbled into greatness with the release of their cover of “Louie, Louie.” The song had originally been a calypso number, written and recorded back in 1958 (a year before the Kingsmen formed) by Richard Berry, a black Los Angeles session player, and released to indifference everywhere except the Pacific Northwest, where it become a regional hit. The area had an especially strong garage rock movement with acts like Paul Revere and the Raiders, the Wailers and the mighty Sonics, a five piece who unleashed furious twin-guitar squall of adrenalized, tightly-controlled r&b stomp into their version of “Louie, Louie.”

The Kingsmen cut was a spontaneous one-take of crashing, at times shambling, cymbals and drums, thick bass, a quick blast of neat guitar and the canonization of a new “beat,” as distinct as Bo Diddley’s. Any doo-wop of previous versions was excised (per the Sonics version) and although the lyrics were innocuous, the vocal was careless, delivered with an adenoidal sneer that slurred the words into incomprehensibility and lent the song to the devices of its youth audience, who believed that dirty words could be deciphered at slower speeds and crafted obscene lyrics, suitable for the raunchy frat parties that were the song’s natural milieu. It broke nationally after a Boston DJ played it all night for the kids, under the mistaken (but well-founded) belief that it would soon be banned from airplay.

“Louie, Louie” entered the Billboard charts in November, 1963 (after being out since May), held the #1 position for two consecutive weeks and stayed on the charts for four months. The subsequent “live” album with dubbed in crowd noise was on the charts throughout 1964.

Promoters pitched Kingsmen concerts as anti-Beatles events (the Pyramids did the same). Before they even hit the road though, the Kingsmen lost their distinctive singer to a power play by the drummer, who had quietly acquired ownership of the band’s name and now wanted to sing. Then J. Edgar Hoover ordered an F.B.I. investigation into whether the band had violated federal laws prohibiting the transport of obscene material across state lines. This involved agents listening to the record at different speeds, filtered through a computer. The bizarre inquiry went on for 31 months before it was finally abandoned with the FBI’s solemn announcement that they couldn’t decipher what he was saying.

The Kingsmen had more hits and their debut single went on to sell over 10 million copies worldwide and become the second-most covered song in rock. It sits higher than all others, including all the Beatles songs ever made, except the one that sits above it, the sonorous “Yesterday.”

_____

____

The other song is “Surfin’ Bird” by the Trashmen. Released by the small Garrett label in the autumn of 1963, it unexpectedly reached #4 by the first week of February, 1964 and went on to sell over a million copies. The surf-rock masterpiece with its senseless (to adults) vocal was recorded two weeks after the JFK assassination. It presents a very different reaction to the shattering event than the old-fashioned goodbye to a girlfriend in “Warmth of the Sun.”

The Trashmen were a young, seasoned garage band that had earned a following in the Minneapolis region by playing school dances, roller rinks, public parks and rented ballrooms. Audiences at these events came to dance; they didn’t stand around gawking at the stage. One night the Trashmen welded a couple Rivingtons songs together and let the drummer have a go at singing. A local promoter got them in a recording studio the next day.

After the song defied all expectations, the band’s cheapskate management wouldn’t pay for the entire group to fly out to Los Angeles for American Bandstand, so drummer Steve Wahrer had to do it himself, lip-synching the track with a microphone and improvising a jerky dance. Afterward, he gave a modest, winning interview to Dick Clark, thankfully preserved on YouTube.

The Trashmen were put on the road for a brutal schedule of small dates by mercenary management, who (like Link Wray’s first record company) lacked respect for the music and undervalued the group’s long-term commercial potential. The Trashmen played around 300 dates in 1964 and the same number again in 1965. After Beatlemania and its attendant mania for all things British, the Trashmen never had another national hit and were soon forgotten by the mass audience. But they continued to release albums true to their musical tastes and styles and had regional success well into the nineteen-sixties.

The hard start/stop rhythm and bizarro singing of “Surfin’ Bird” proved enduring. The song didn’t need any alteration when the Ramones made it a permanent fixture of their live shows at early annihilating performances at CBGB’s in the mid-Seventies. After Stanley Kubrick used the song in Full Metal Jacket, it became a seemingly indelible feature of any movie or video game about the Vietnam War. The Trashmen catalog continues to grow in stature and is well-represented by the comprehensive and meticulous re-issues put out by Sundazed.

The Beatles could profess honest admiration for their rockabilly era heroes or the Beach Boys or Motown, but the new, hard garage rock put them off. During a radio interview in New York on that first tour, Ringo Starr used his time to sniff to the listening audience that he did not like the Trashmen.

____

“Louie, Louie” and “Surfin’ Bird” are just two examples of the brash American rock and roll that was developing free of Beatles influence. Another is the catalog of Bobby Fuller, a singer/guitarist who started releasing singles that he recorded in a makeshift but impressive studio that he constructed in his parents’ home as a teenager in El Paso, Texas. Fuller’s truly D.I.Y. career (from 1961 to 1966) started yielding national hits as soon as he moved to Hollywood and signed with a label.

Fuller always idolized fellow West Texan Buddy Holly and shared Holly’s taste for melody and brevity. Fuller also had a strong background in surf guitar and could peel off bold, reverb-laden solos with abandon. He was rhythm-heavy player with meticulous craftsmanship, sharp pop sensibility and a distaste for the self-indulgent rock and hippie style of the day. Fuller prided himself and his band on keeping things tight and maintaining what he considered a sharp appearance. Its hard to think of any other rock star of 1966 who went onstage dressed like a regular person without some variant of a moptop.

_____

_____

Appropriately, Bobby Fuller’s first national hit was “I Fought the Law,” a song written by Sonny Curtis, Buddy Holly’s friend who joined the Crickets after Holly’s death. To detractors, Fuller is merely a square, a Buddy Holly wanna-be completely out of step with the dawning Age of Aquarias, a ghost from the previous decade. But then why did he sell so many records?

Del- Fi was a small label with mob associations that recorded bands at P.J.’s Lounge for its “Live at P.J.’s” series and cut deals with radio stations to co-sponsor albums. Hence, Bobby Fuller’s stunning full-length debut in 1965, an LP of his best songs and blistering surf/hot rod instrumentals, was titled KLRA, King of the Wheels, undercutting the rewarding material within. On “Let Her Dance,” for example, swelling choruses and chiming percussion over a narrow, Tex-Mex guitar line create a Phil Spectoresque wall of sound, as Fuller sings in a twangy holler about seeing an ex out with someone else and having a more sanguine reaction than the typical rage or self-pity of nearly all pop songs. Other songs from the KLRA album showcase Fuller’s rich voice and affirmation of American rock and roll roots. A year after his death, Creedence Clearwater Revival would start mining the same vein to great success.

1966 should’ve been a year of triumph. “I Fought the Law” became a huge hit and its classic accompanying album banged up the charts, but Fuller was still working a small-time circuit and not seeing much money. He was displeased with what would be his final studio sessions, produced by a young Barry White, whose arrangements Fuller rightly found too saccharine. His band members quit and he had to find replacements. But he was also having fun and neither depressed nor a depressive.

On July 18, 1966, Bobby Fuller, was found dead in the front seat of his car in front of his apartment in L.A. He was 23 years old. Fuller’s rigor-mortised body was thoroughly soaked with gasoline and bruised about the face and hands. Gasoline had been poured down his throat. The coroner unconvincingly labeled his death a suicide, then a self-inflicted accident. It was rumored to be a mob-killing, possibly over a moll, but other speculation persists. Fuller’s brief, productive life had ended in a horrifying torture-murder. His killer has never been identified.

______

In summation, rock and roll was doing fine without the Beatles when they broke the U.S. market. They weren’t the first rock act to write their own lyrics and their lyrics didn’t break any new ground in terms of innovation or content. They weren’t better than the brash and brave originators who preceded them. Live, they were always a tepid proposition. George Harrison was an exceptionally dull guitarist who spent a lot of time with Eric Clapton and turned the psychedelic-blues axeman into a dull guitarist. Uniformly weak instrumentalists, the Beatles were unable to cut loose with the precision and abandon of their contemporaries of 1964 or a later powerhouse like Creedence, who had been playing together since 1959 and whose leader wrote better songs than Lennon and McCartney.

The Beatles ceased all live performances after the disastrous 1966 world tour, where they were again surpassed by America’s lost band the Remains who opened for them on the U.S. leg of the tour (the teenage Johnny Ramone attended the Shea Stadium concert with a bag full of rocks to throw at the Beatles) and almost killed by angry crowds in the Philippines after they snubbed Imelda Marcos. As a non-gigging band, the Beatles grew even more reliant on the ideas and techniques of establishment producer George Martin. Regarding any claims that the Beatles brought avante-garde techniques or sensibilities (gleaned from gallery walks and the diversions of the upper class society crowd the group now ran with) into rock and roll, there’s little evidence of it. The Beatles -and all of the 60’s bands, really – were far outpaced in this area by the confrontational Doors, whose dissolute leader had a genius I.Q.

The Beatles weren’t better than the new American bands breaking into the U.S. market in 1964 and they didn’t get popular because they were making better rock and roll. They were just a merseybeat band with the backing of a large multinational corporation that had decided to invest in them. Capitol Records got the Beatles on the radio and brought the band stateside. Brian Epstein sparked a promotional frenzy in the States when he ineptly assigned 90% of the profits from the sale of Beatles merchandise to the maker of such product. The resulting explosion of hysterical Beatlemania marginalized the dynamic and evolving rock and roll music of America in favor of establishment-endorsed Beatles product.

The contribution of the Beatles to the music of rock and roll has always been grossly overstated by the band’s acolytes who now run the business of rock. Their great talent was their portability. Musically, they were conventional and old-fashioned compared to their forerunners or contemporaries. They jumped on every musical trend at its tail-end and got credit for innovation. They were not impressive live and quit just as their quaintness was being made apparent by the thunderous Led Zeppelin (who, interestingly, Elvis Presley got on with very well)

Brian Epstein was the architect of the Beatles success. He softened the Beatles music by moving them away from the r&b and Gene Vincent material and having them sing showtunes, which was most of what they recorded when he landed them a studio audition at Decca Records. Pop showtunes are what Epstein had an ear for and Paul McCartney proved to be an avid student and composer of this stuff. Epstein softened the band’s appearance by discarding the severe black leather and instituting constant smiles (especially while singing), poodle haircuts, and a new non-threatening wardrobe (e.g. the womanly collar-less suits). The overall effect of the changes was to feminize the Beatles.

_____

_____

Despite his inept contract negotiations, Epstein, it turned out, had excellent commercial sense. The great success of the Beatles stems directly from his intervention (Brian Epstein was the first “boy band” manager). He also respected the music and was convinced of the band’s long-term commercial potential before anyone. He was financially fair and honest with the Beatles, as well as the other bands that he managed. It’s safe to say that Epstein was in love with the Beatles, not just in a platonic way. It’s likely that he and John Lennon had some type of sexual relationship around the time they vacationed together in Spain in 1963.

Beatlemania made Epstein a wealthy man and gave him the freedom to live however he wanted. He developed a drug problem and got further into kinky, anonymous roughtrade sex. He was broken by the 1966 tour disaster in the Phillipines and the band’s subsequent decision to quit touring, as it ended his usefulness to them. Brian Epstein died in August, 1967, an apparent prescription drug overdose.

John Lennon is the other tragedy of the Beatles. A poor guitarist, he made up for it with an excellent voice and razor wit. Lennon tends to be author and lead vocal on the great Beatles songs that exist, like: “Help!,” “I Am The Walrus,” “Come Together,” the Epstein-inspired Dylan imitation “You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away,” and his contributions to the White Album. The angriest Beatle, Lennon wrote the best Beatles songs and sang rock music with the most conviction.

The tragedy is that Lennon lost control of his band to Paul McCartney and Brian Epstein and George Martin and grew to hate everything about the group after the Epstein makeover. Lennon always preferred being a wild leather pill-popping rocker doing whatever he wanted to the smiling, polite, suited “Beatle John” role he had to play. His drug dependency increased as the band slipped further away and his role as leader ended

After the Beatles, Lennon put out one excellent, stark solo album John Lennon: Plastic Ono Band and embarked on a career of dull, inconsequential music and political posturing, inspired and manipulated by the far craftier Yoko Ono. Lennon changed considerably during the Beatles run, from the cheerily sardonic, slightly puffy presence at the start of Beatlemania to an emaciated, drug-addled neurotic mess by the end, chained to Yoko Ono and lacking humor. While normal maturation may account for some change, Lennon’s personality was also likely affected by his abuse of hard drugs, particularly the massive amounts of powerful LSD he began taking in 1966, a period during which Lennon later claimed he was trying to eradicate his personality through use of the drug.

He couldn’t wipe out the truth. Lennon pulled the curtain back on the Beatles Myth in a two-part interview in Rolling Stone at the start of 1971, where he lathered contempt on McCartney, Epstein and all of the Beatles fans, who he termed “an ugly race” and dismissed hippies as “uptight maniacs going around wearing fucking peace symbols.”

Regarding his Beatles tenure, Lennon summed it up: “I resent performing for the fucking idiots.”

Clearly this person has an inability to escape an era. Claiming that the Beatles are not rock’n’roll but only under the assumption that the Beatles would even care. Maybe it’s the Beatles that lead us out of rock’n’roll, to which I say thank goodness. I mean c’mon, who in their right mind would want to listen to Chuck Berry today when you have The Talking Heads, Radiohead, David Bowie, or hell, even Kanye West. That’s what the Beatles paved the way for, sorry. Pop music, in a general sense, got better.

I like the general tenor and hard-hitting straightforward style of this writer.